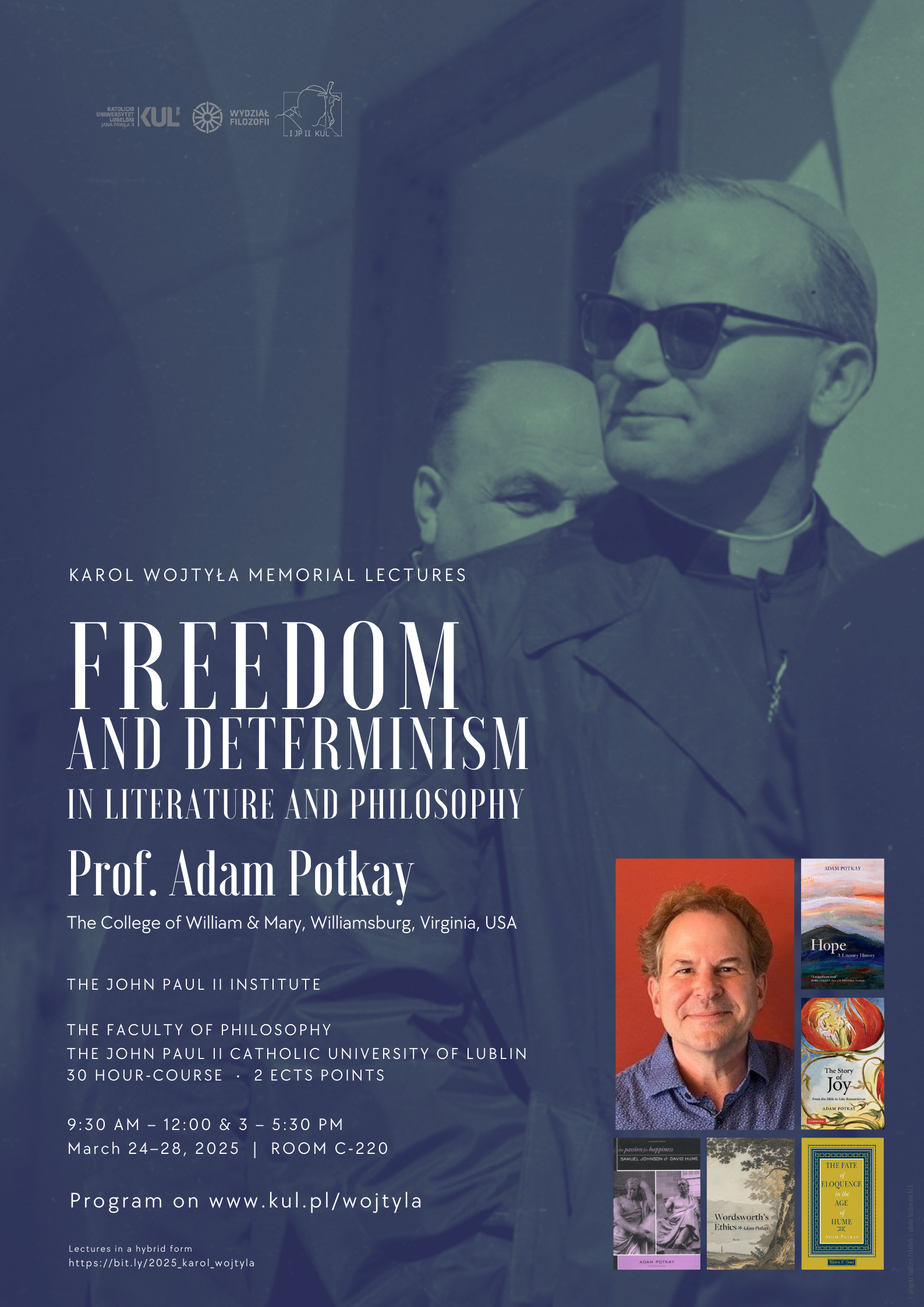

Karol Wojtyła Memorial Lectures

Freedom and Determinism in Literature and Philosophy

Prof. Adam Potkay

William & Mary University, Virginia, USA

The John Paul II Institute

The Faculty of Philosophy

The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin

March 24-28, 2025 30 Hour-Course 2 ECTS Points

9.30 am – 12:00 pm & 3 – 5.30 pm

Room C-220

Lectures in a hybrid form

https://bit.ly/2025_karol_wojtyla

Outline of introductory lecture, “Karol Wojtyła and Max Scheler on Freedom and Determinism,” and Overview of Lectures

As a philosopher and theologian, Karol Wojtyła insisted on the freedom of the person, specifically the freedom of the person through his experienced freedom of intellect and will, and the willful control of non-rational appetites and passions. Wojtyła built much of his philosophy in engagement with Max Scheler (1874-1928), who was for most of his career a Catholic phenomenologist and professor of philosophy at Cologne. Scheler is a foundational figure in what is known as “Lublin Thomism,” the attempt to marry Thomist theology with phenomenological philosophy. There is for Scheler, as for Aquinas and Wojtyła, an objective hierarchy of values according to which our actions are to be judged: an order rising from pleasure/displeasure through values that are life- or health-enhancing, then ‘spiritual’ values (including aesthetic and moral values), and finally, the highest modality of the holy and unholy. A good person’s order of values will be identical to this objective order.

Karol Wojtyła agreed with Scheler up to this point—but objected to his ethical emotionalism. For Scheler, who built—I will argue—on nineteenth-century English and German Romantics—values are feelable phenomena. These feelings lie below the level of willing or acting, though they may result in actions. Scheler calls our basic ethical response “emotional intuitions,” which come in the forms of love or hate towards a person or deed. If we love correctly, we are good persons; our intuitions correspond to the objective hierarchy of values now seen as an ordo amoris or ‘order of love.’

Wojtyła, in the lectures he delivered in Lublin between 1954-57, endorses much of Scheler’s philosophy, but not his ethical emotionalism. Scheler was right, he maintains, in holding we may intuitively find not only objective values but indeed the Thomistic hierarchy of values from bodily pleasure to deep holiness. But he was not right that intuitionism is a sufficient basis for ethics. For how can the passive reception of value account for the person’s willing the good, his self-conscious ethical action? And is this reception of value even possible without a prior, active judgment about what a value is?

Wojtyła might have noted that these problems extend, in some sense, back to the English and German Romantic poets, some of whom I will address later in these lectures—focusing on William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. But Wojtyła, as a poet himself, knew that artistic phenomenology and the reverential mysteries poetry can disclose a different sphere than argumentative philosophy. As a philosophical phenomenologist, however, it is incumbent on Scheler to explain how one can get from knowing values (cognition) to actively willing those values (volition), and for Wojtyła Scheler’s philosophy is unable to do so; it is the will, and the agent’s self-actualization in willing as well as judging the good, that Wojtyła himself emphasizes in his early lectures through to his major treatise, The Acting Person(Polish edition, 1969).

Wojtyła’s opponent in all of this is causal and moral determinism. Determinism sees the individual as a subject, subjected to chains of prior causes and external influences that downplay or eliminate the will and its supposed freedom. Determinism, as I will show in these lectures, goes back to Homer’s Iliad and then ancient, pre-Christian philosophy and world views, most notably Stoicism. Materialist determinism was recurrent in modern empiricist philosophy after Thomas Hobbes, and will flourish in the mechanistic philosophies and literary movements of the nineteenth century: especially, we shall see, Bentham’s utilitarianism; Zola’s literary naturalism; and Marx’s view of history. Determinism is still a force to be reckoned with today in politics as well as philosophy—in behaviorism, evolutionary biology and phylogenetic determinism, “victimization” claims, the exteriorization of blame, and abdication of personal responsibility.

But while Wojtyła rejects causal determinism of a post-Hobbesian variety, he accepts another kind of determinism, an inheritance from Aristotelianism, ancient Stoicism and Thomism: teleological determinism. That is, although there are free persons, they are determined by a pre-given human/cosmic aim or telos; they must become what they are by nature or design meant to be. Teleology that rises from biology (a fetus is by nature designed to become an adult) to ethics (an adult, having both reason and sociability, is meant to be sociable/oriented towards common good), to politics (what is the best government for establishing the common good), to the cosmos (providence, all happening for the greatest overall good—a tenet from Stoicism to Christianity).

I offer this lecture series on the history of determinism and of freedom, from the ancients to Karol Wojtyła, to make historical sense of his intervention in this most important of human discourses. My seven remaining topics/nine lectures are:

- 2, Ancient Determinism (Iliad to the Stoics);

- 3, Christian Theology and free will (Augustine through Milton’s Paradise Lost);

- 4-5, Modern Determinism, two lectures, on Hobbes through literary naturalism (Zola, Richard Wright);

- 6-7, Romanticism and ethical intuitionism, two lectures, focusing on short poems by Coleridge and Wordsworth (and touching upon Coleridge’s Trinitarian turn), with reference to Scheler on feelings;

- 8, Freedom and Necessity as the novelistic topic of Tolstoy’s War and Peace;

- 9, Freedom and the contrarieties of the human person in Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov (with a coda on Karol Wojtyła’s play The Jeweler’s Shop);

- 10, A coda on the freedom evidenced by certain types of literary wit and humor—I will refer here to parts of Shakespeare and also Gombrowicz’s novel Ferdydurke. I am inspired in this last section by a recent essay by Pope Francis, “There is Faith in Humor”: humor lifts others and is a medicine for ourselves. Francis tells this story about Wojtyła’s humor: in a preliminary session of a conclave, the young Cardinal was chided by a senior colleague for his athleticism—wasn’t this infra dig? Should a priest really ski and hike, swim and bike? Wojtyła replied: “But do you know that in Poland these are activities practiced by at least 50 per cent of cardinals?” In Poland at the time there were only two cardinals.

Phenomenologically, perhaps it is in humor and wit that freedom may most clearly be seen. Verbal and creative wit do not seem to be caused, but rather testify to a person actively associating and acting.

Ostatnia aktualizacja: 23.03.2025, godz. 00:58 - Andrzej Zykubek